Describing the dynamics of the Polar Vortices

The dynamics of the stratospheric polar vortex are a balance between the effects of radiative transfer (which tends to strengthen the vortex), and the dynamical effects of Rossby waves (which are usually thought of as weakening the vortex, but whose role is a bit more complicated). The sources of the waves are in the troposphere below: flow over planetary-scale mountain ranges like the Rockies and Himalayas, and variations in diabatic heating that arise from land-sea contrasts. These departures from longitudinal symmetry are more pronounced in the Northern Hemisphere, leading to systematic differences between the polar vortex in each hemisphere.

The evolution of the vortex is highly variable: the waves and the vortex are constantly shifting in strength and structure. While some of this variability can be traced to variations in the tropospheric sources, much of it also seems to arise from the chaotic interplay between the vortex and the waves.

A reductionist approach to studying this highly complex system is to try capture the elements of this system in a simpler context that can be more easily analyzed. To this end, one can describe the vortex as a single, sinusoidal Rossby wave propagating on a near-circular vortex described by a single contour that describes the vortex edge.

This can be combined with a representation of the interation between the wave and the vortex, resulting a set of three equations (Hitchcock 2021):

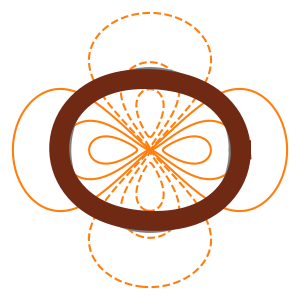

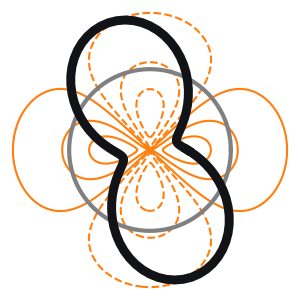

$$ \frac{da}{dt} = -a + \sin \phi \\ \frac{d\phi}{dt} = \hat{S} (\Delta - \hat{\delta}) + \frac{\cos \phi}{a} \\ \frac{d\Delta}{dt} = \hat{\gamma} (1 - \Delta - \hat{\kappa} a^2 \Delta) $$The three degrees of freedom correspond to the amplitude \(a\) and phase \(\phi\) of the wave, and the strength of the potential vorticity jump at the edge of the vortex \(\Delta\). This can be thought of as the strength of the vortex. These are depicted in the figure above.

Steady States

One of the appeals of this approach is that it can suggest what parameters might play key roles in determining the character of polar vortex variability. Four non-dimensional parameters arise. \(\hat{\kappa}\) sets how strongly the wave is forced by tropospheric sources. \(\hat{S}\) and \(\hat{\delta}\) determine how the phase speed of the Rossby wave mode depends on the potential vorticity jump \(\Delta\): when \(\Delta = \hat{\delta}\), the wave mode is stationary and can be resonantly excited by a stationary forcing. The final parameter \(\hat{\gamma}\) is a ratio of relaxational timescales and plays a relatively minor role.

The vortex described by these equations has steady states when the potential vorticity jump satisfies the cubic polynomial

$$(\Delta - 1)(\Delta - \hat{\delta})^2 + \hat{S}^{-2} (\Delta - 1 + \hat{\kappa} \Delta) = 0$$This has either one or three solutions, depending on the non-dimensional parameters. When there are three solutions, one is always unstable, while the other two correspond to a strong vortex with a weak wave, and a weak vortex with a strong wave. In the left figure above, the wave amplitude is weak, and the vortex is near-circular. The potential vorticity jump at the edge of the vortex is strong, as is indicated by the width of the contour. In the right hand figure above, the wave amplitude is large and the vortex is distorted; the potential vorticity jump is weak, indicated by the thin contour.

Chaotic Evolution

For larger values of \(\hat{S}\) when the dynamics of the wave are more sensitive to the state of the vortex, the weak vortex state loses stability, and the vortex starts to exhibit internally generated variability. For some values, this variability is chaotic, evolving irregularly despite the fact that the external forcing of the wave is stationary. An example of such a chaotic trajectory is shown in the animation. In the animation the width of the contour indicates the strength of the potential vorticity jump while the colour indicates the direction of the phase speed of the wave: blue colours indicate westward propagation, black colours are near-stationary, and red colours indicate eastward propagation. Note that the wave tends to amplify when the wave is near stationary, and when it is in a particular phase relative to the topography. The splitting of the real vortex also tends to occur at a particular orientation relative to the distribution of the continents in the Northern Hemsiphere as well.

Further Directions

As one might imagine, the time-averaged strength of the vortex is sensitive in this model to both the topographic forcing \(\hat{\kappa}\) as well as to the internal dynamics of the vortex (here represented by \(\hat{S}\) and \(\hat{\delta}\)). The most interesting insight from this model to me was that in the dynamically active part of the phase space, it is the location of the resonant value of the potential vorticity jump \(\hat{\delta}\) that has the most direct control over the mean state of the vortex. This suggests that understanding how climate change might affect the mean state of the stratospheric polar vortex might be better understood through understanding the dynamics of the waves on the vortex edge rather than by understanding how the forcing might change. Ongoing work is trying to extend this result to more realistic representations of the vortex.